[:en] On Christmas 1915, with the war firmly entrenched in deadlock and the August enthusiasm of 1914 a bittersweet memory, with an ever-increasing defensive posture of German intellectuals towards Allied accusations of “barbarianism,” Rudolf Eucken published a popular presentation of German thought, Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus. At the outbreak of the war in 1914, Eucken was arguably the most internationally recognized living German philosopher: he had received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1908; he had toured the United States in 1913 as visiting professor at Harvard University; he met Henri Bergson at Columbia University; most of his works had been translated into English and French. In August 1914, Eucken became one of the most vocal supporters of the German war-effort and a leading figure in the spiritual mobilization of German intellectuals.

On Christmas 1915, with the war firmly entrenched in deadlock and the August enthusiasm of 1914 a bittersweet memory, with an ever-increasing defensive posture of German intellectuals towards Allied accusations of “barbarianism,” Rudolf Eucken published a popular presentation of German thought, Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus. At the outbreak of the war in 1914, Eucken was arguably the most internationally recognized living German philosopher: he had received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1908; he had toured the United States in 1913 as visiting professor at Harvard University; he met Henri Bergson at Columbia University; most of his works had been translated into English and French. In August 1914, Eucken became one of the most vocal supporters of the German war-effort and a leading figure in the spiritual mobilization of German intellectuals.

Unlike Christmas 1914, which occasioned a not insignificant number of fraternizations and ceasefires along the stretch of the Western Front, Christmas 1915 witnessed a drastic curb in such spontaneous acts of fraternity across enemy lines. Military command on both sides had issued orders against such Christmas truces. As Llewelyn Wyn Griffith reports in his war-memoirs Up to Mametz, his brigade commander (15th Royal Welch Fusiliers) forbade any exchange of gifts with German soldiers and, indeed, ordered the resumption of firing on Christmas day. On the home fronts, Christmas song books, cards, and other uplifting materials were produced to bolster the morale of troops at the front.

In Germany, this war-time orchestration Christmas included Eucken’s Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus. 30,000 copies of the book were sold, with numerous copies dispatched to the front. As Eucken reports in his Lebens-Erinnerungen. Ein Stück deutschen Lebens: “Zugleich habe ich auch literarisch alle Kraft und Mühe daran gesetzt, unser Volk in der Kriegszeit zu fördern. So erschien gleich nach Kriegsausbruch die Abhandlung ‘Die weltgeschichtliche Bedeutung des deutschen Geistes’, ferner zu Weihnachten 1915 die Schrift ‘Die Träger des deutschen Idealismus’, die einen großen Erfolg hatte und durch einen geschickten Vertrieb rasch in die Hände vieler Krieger kam (es wurden im Krieg nicht weniger als 30,000 Exemplare abgesetzt).” Published in handy paper-back, ideal for carrying at the front, and dedicated to “his two beloved sons, Arnold and Walter, both serving in the field,” Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus does not propose, as Eucken writes in his introduction, any “scientific contribution” to the understanding of German philosophy, but speaks instead directly to the German people, who are engaged “in our violent times” with full heart and soul. As he writes: “Ungeheures geht bei uns vor, Ungeheures müssen wir wirken und leiden, Ungeheures fordert von uns die eherne Gegenwart. Um dem gewachsen zu sein, bedürfen wir nicht nur seelischer Kraft, sondern auch eines freudigen Vertrauens auf unser Volk, auf seine Tüchtigkeit und seine Größe.”

In Germany, this war-time orchestration Christmas included Eucken’s Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus. 30,000 copies of the book were sold, with numerous copies dispatched to the front. As Eucken reports in his Lebens-Erinnerungen. Ein Stück deutschen Lebens: “Zugleich habe ich auch literarisch alle Kraft und Mühe daran gesetzt, unser Volk in der Kriegszeit zu fördern. So erschien gleich nach Kriegsausbruch die Abhandlung ‘Die weltgeschichtliche Bedeutung des deutschen Geistes’, ferner zu Weihnachten 1915 die Schrift ‘Die Träger des deutschen Idealismus’, die einen großen Erfolg hatte und durch einen geschickten Vertrieb rasch in die Hände vieler Krieger kam (es wurden im Krieg nicht weniger als 30,000 Exemplare abgesetzt).” Published in handy paper-back, ideal for carrying at the front, and dedicated to “his two beloved sons, Arnold and Walter, both serving in the field,” Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus does not propose, as Eucken writes in his introduction, any “scientific contribution” to the understanding of German philosophy, but speaks instead directly to the German people, who are engaged “in our violent times” with full heart and soul. As he writes: “Ungeheures geht bei uns vor, Ungeheures müssen wir wirken und leiden, Ungeheures fordert von uns die eherne Gegenwart. Um dem gewachsen zu sein, bedürfen wir nicht nur seelischer Kraft, sondern auch eines freudigen Vertrauens auf unser Volk, auf seine Tüchtigkeit und seine Größe.”

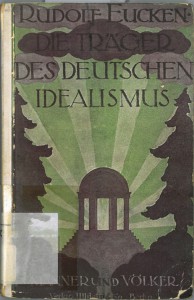

As with his public 1914 lectures, Die sittlichen Kräfte des Krieges and Die weltgeschichtliche Bedeutung des deutschen Geistes, Eucken seeks in this 1915 work to instill assuredness in the cause of the German war-effort by revealing the deeper meaning of Germany’s existential struggle. That meaning is immediately announced in both the title and the cover of Eucken’s Christmas offering. In Eucken’s title, the term Träger (“bearer” or “carrier”) suggests a host of imbricated meanings: German thinkers are the “bearers” of the German Spirit; German Idealism is the “bearer” of the German Nation; and those in the field, as with his two sons, are the Christ-like “bearers” of Germany’s “world-historical mission” and salvation. This multi-faceted term Träger implicates the book itself as a physical object. Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus is meant to be carried into the field while the act of its reading is meant to support the spiritual Innerlichkeit of German soldiers, who now shoulder the burden of Germany’s metaphysical promise. Even before the book is opened, a prospective reader is told what is at stake in the war through a visual quotation from Fichte’s Reden an die deutsche Nation: “The dawn of the new world has already broken; already, it gilds the mountain peaks and forms the coming day. I want to catch the rays of this dawn, if I can, and press them into a mirror in which the disconsolate age can see itself, so that it might believe that it is still there.” Eucken’s book-cover in this manner mirrors the vision of Fichte’s original address while simultaneously motivating its imminent realization. In these various senses, Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus is an exhortation to carry forth a new form of life through the “agency” and “suffering” (Wirken und Leiden) of das Werk des Krieges.

Within the broad sweep of Eucken’s survey of German Idealism, his chapter on Fichte provides its center of gravity. Fichte is characterized as “the first thinker of the German people (Volk)” whose thinking speaks to “the present political situation and question of the Nation” and who “hits on the heart of matter” (der Kern der Sache) in recognizing Innerlichkeit as the “original creation of the German people.” Fichte’s spiritual mantle is inherited from Luther, to whom Eucken bestows the honor of the “the most original witness” of German Innerlichkeit as a “care for the salvation of the soul” (Sorge für die Rettung der Seele). To define life through Innerlichkeit is to define life through its care for eternity, and it is this care for the soul that is carried forth with the historical mission of the German Nation. As Eucken observes, although Fichte witnessed the collapse of an “ancient system of states” (the Holy Roman Empire, dissolved by Napoleon in 1806) and Prussia’s humiliating military defeat, his faith (Glauben) and assuredness (Vertrauen) in the German people and its spiritual destiny nonetheless remained unfazed. Amidst this catastrophe, Fichte stood “true to his people” and internalized the “general emergency” of the German Nation as “his own personal affair.” He did not react in “resignation and complaint,” but responded with courage in addressing “his people” and providing “for the first time a principled philosophical justification” for the idea of the Nation. Eucken’s acclaim of Fichte’s resoluteness indirectly calls upon his own audience in 1915 to remain steadfast in the aftermath of 1914 and the failure of the optimistic Schlieffen Plan, irremediably checked at the Battle of the Marne.

Eucken employs the Reden an die deutsche Nation as both a mirror and a vision for his own war-time exhortation. On the one hand, Eucken projects onto Fichte’s historical situation of 1807-1808 his own historical condition of 1915. Fichte’s Reden provides in this manner a kind of mirror for a reflection on the present existential struggle of the German Nation and Spirit. On the other hand, Eucken lauds Fichte’s philosophical resolve and response to the catastrophe of 1806 as a guiding vision for the future of the present war. This double-vision, albeit from two converging historical perspectives, 1807 and 1915, allows for a double-reading of Fichte’s Reden such that Eucken can in the same breath speak to the present through Fichte while speaking of Fichte from the present. The over-all effect of this rhetorical fashioning is a temporal foreshortening meant to reveal Fichte’s proximity, the sense in which, as Husserl remarked in his own Fichte lectures, der Fichte der Befreiungskriege spricht zu uns. Yet, this foreshortening equally motivates an anticipatory resoluteness towards the manifest destiny of the German Nation, as originally envisioned by Fichte, and which the present war promises to accomplish. What might (or must) appear to us (in 2015) as a flagrant projection of Eucken’s own historical present onto Fichte’s past must have appeared to his readers in 1915 as a reassuring and emboldening legitimation of their present struggle. Eucken’s double-vision reflects the multi-faceted logic of “support” or “bearer” that operates through-out Die Träger des Deutschen Idealismus. Fichte’s philosophical struggle and the 1813 Befreiungskriege legitimate the struggle of 1915, which, in turn, must carry forth the “world-historical mission” of the German Spirit and Nation launched in the aftermath of the catastrophe of 1806, and, which, with an even deeper resonance, brings to completion the original impulse of the German spirit in Luther’s Reformation.

A philosopher of the people who engages himself in time of war is a philosopher who must equally volunteer to die for his people. In 1813, as Eucken observes, Fichte would have preferred to see service in the field and served in the Prussian Landsturm “to the best of his abilities.” Fichte managed to enlist as a Landsturmmann along with other university professors, the entire group cutting a comical image as soldiers; in the report of one observer, “[man] kaum dencken konnte dass sie Soldaten wären.” Even though Fichte did not participate in any actual combat, Eucken implicitly suggests that his death in 1814 should be considered indirectly as a sacrifice for the nation, where Eucken’s proposition subtly turns on the double-meaning of the German word Opfer, meaning both “victim” and “sacrifice.” Fichte died on January 17, 1814 after contracting typhus from his wife, Johanne, who served in a military hospital; in this sense, Fichte fell as a “victim” of the war (als ein Opfer des Krieges gefallen). One cannot help but also hear the implication that Fichte’s death was also a “sacrifice.” Insofar as Fichte’s life and thinking understood itself as an unambiguous testimony and evidence (ein deutliches Zeugnis) for truth of the German Spirit, Fichte’s entire life and thinking embodies the work of sacrifice. In Eucken’s words: “Eine grosse Krise wies ihm [Fichte] die Aufgabe zu, sein Volk zu wecken und zu sammeln, er hat diese Aufgabe durch sein ganzes Wirken und Sein in hervorragender Weise gelöst, dem Aufstieg deutschen Wesens bleibt sein Name unzertrennlich verbunden.” In the final hour of his death, as Landsturmmann, University Professor, and Philosophicus Teutonicus, Fichte spent his last breath with an image of his promised land before him. As Eucken notes: “Noch seine letzten Phantasien beschäftigten sich mit dem Vaterland und dem Vordringen der deutschen Heere.”

A philosopher of the people who engages himself in time of war is a philosopher who must equally volunteer to die for his people. In 1813, as Eucken observes, Fichte would have preferred to see service in the field and served in the Prussian Landsturm “to the best of his abilities.” Fichte managed to enlist as a Landsturmmann along with other university professors, the entire group cutting a comical image as soldiers; in the report of one observer, “[man] kaum dencken konnte dass sie Soldaten wären.” Even though Fichte did not participate in any actual combat, Eucken implicitly suggests that his death in 1814 should be considered indirectly as a sacrifice for the nation, where Eucken’s proposition subtly turns on the double-meaning of the German word Opfer, meaning both “victim” and “sacrifice.” Fichte died on January 17, 1814 after contracting typhus from his wife, Johanne, who served in a military hospital; in this sense, Fichte fell as a “victim” of the war (als ein Opfer des Krieges gefallen). One cannot help but also hear the implication that Fichte’s death was also a “sacrifice.” Insofar as Fichte’s life and thinking understood itself as an unambiguous testimony and evidence (ein deutliches Zeugnis) for truth of the German Spirit, Fichte’s entire life and thinking embodies the work of sacrifice. In Eucken’s words: “Eine grosse Krise wies ihm [Fichte] die Aufgabe zu, sein Volk zu wecken und zu sammeln, er hat diese Aufgabe durch sein ganzes Wirken und Sein in hervorragender Weise gelöst, dem Aufstieg deutschen Wesens bleibt sein Name unzertrennlich verbunden.” In the final hour of his death, as Landsturmmann, University Professor, and Philosophicus Teutonicus, Fichte spent his last breath with an image of his promised land before him. As Eucken notes: “Noch seine letzten Phantasien beschäftigten sich mit dem Vaterland und dem Vordringen der deutschen Heere.”